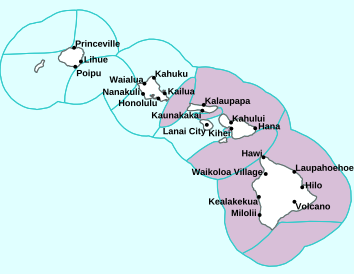

Air Temperatures – The following high temperatures (F) were recorded across the state of Hawaii Wednesday…along with the low temperatures Wednesday:

82 – 73 Lihue, Kauai

83 – 73 Honolulu, Oahu

84 – 62 Molokai AP

85 – 60 Kahului AP, Maui

83 – 68 Kailua Kona, Hawaii

81 – 65 Hilo, Hawaii

Here are the latest 24-hour precipitation totals (inches) for each of the islands Wednesday evening:

0.98 Mount Waialeale, Kauai

0.40 Waihee Pump, Oahu

0.00 Molokai

0.00 Lanai

0.00 Kahoolawe

0.07 Puu Kukui, Maui

0.26 Kawainui Stream, Big Island

The following numbers represent the strongest wind gusts (mph) Wednesday evening:

20 Waimea Heights, Kauai

22 Kii, Oahu

24 Molokai

23 Lanai

39 Kahoolawe

25 Kahului AP, Maui

30 Kealakomo, Big Island

Hawaii’s Mountains – Here’s a link to the live webcam on the summit of our tallest mountain Mauna Kea (nearly 13,800 feet high) on the Big Island of Hawaii. Here’s the webcam for the 10,000+ feet high Haleakala Crater on Maui. These webcams are available during the daylight hours here in the islands, and at night whenever there’s a big moon shining down. Also, at night you will be able to see the stars, and the sunrise and sunset too…depending upon weather conditions.

Aloha Paragraphs

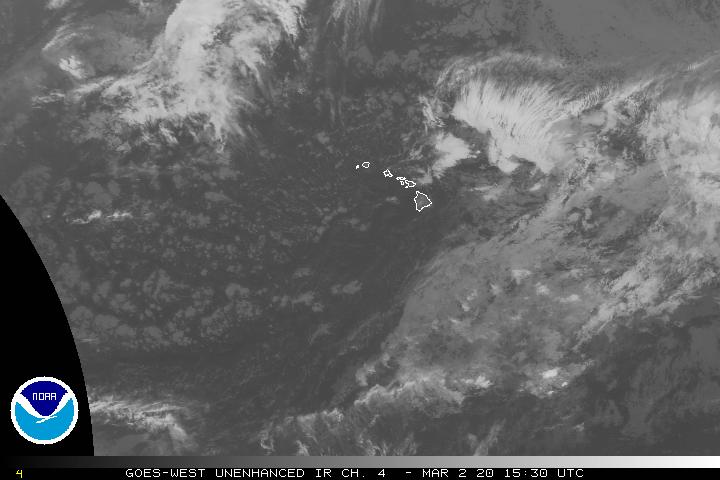

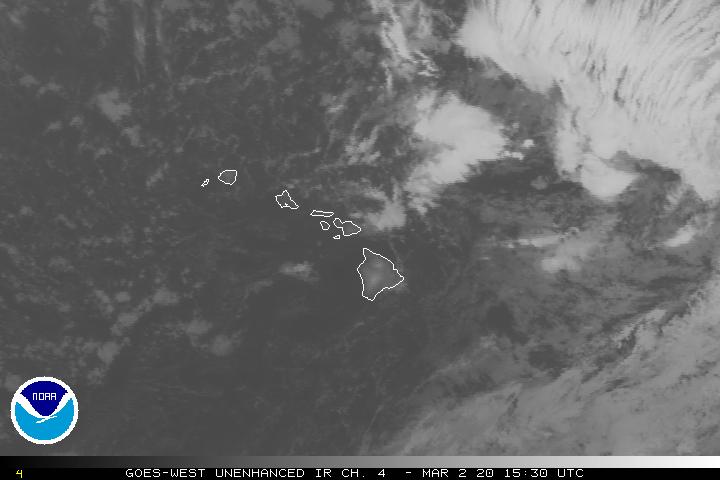

Low pressure with an associated cold front northwest

(click on the images to enlarge them)

Deep clouds to the northwest…and south

Clear to partly cloudy…cloudy areas mostly windward

Showers locally – Looping image

There are no advisories or warnings

~~~ Hawaii Weather Narrative ~~~

Broad Brush Overview: Trade winds weaken and shift out of the south and southwest Thursday through Friday, as a cold front approaches and moves into the area from the northwest. Increasing moisture and light winds ahead of this front will bring warm and muggy conditions with increasing rain chances late Thursday through Saturday. A trough aloft could trigger a few thunderstorms along and ahead of the front, especially over the northwest islands Thursday night into Friday. A gradual drying trend from west to east, with a return of moderate to strong trades is expected by the end of the weekend and early next week…as high pressure builds north of the state.

Details: The models show a change tonight through Thursday, as an upper trough approaches and moves into the state. An associated cold front will advance eastward toward the islands through Thursday, then move down the island chain Friday into the weekend. Trades will begin to soften and shift south tonight, potentially becoming light and variable locally. The pool of deep tropical moisture associated with the front will shift eastward over the northwest islands Thursday night, then over the rest of the state Friday through Saturday…as the front begins to move through. This moisture will support increasing rainfall chances Thursday night over Kauai and Oahu.

Looking Ahead: As we push into the weekend through early next week time frame, the models suggest a gradual drying trend in the wake of the cold front from west to east. Cooler northerly winds will fill in over the western end of the state beginning Saturday, then quickly shift to a more typical trade wind pattern Sunday night into early next week, as high pressure builds to the north. The cold front is forecast to stall and dissipate around the Big Island through the second half of the weekend, which would result in higher rainfall chances lingering for the eastern part of the state.

Here’s a near real-time Wind Profile of the Pacific Ocean – along with a Closer View of the islands / Here’s the latest Weather Map / Here’s the latest Vog Forecast Animation / Here’s the Vog Information website

Marine Environmental Conditions: A high to the north will maintain locally strong northeast trade winds over Hawaiian coastal waters. Winds will veer southeast and weaken tonight, as a front approaches from the west. The winds will veer out of the south Thursday as the front moves closer, then shift out of the north behind the front Friday night. A new high will build east behind the front and produce locally strong northeast trade winds over Hawaiian coastal waters starting early next week.

The current large northwest swell will continue to subside over the next few days. Surf should drop below advisory thresholds tonight. A series of moderate northwest swells are expected through the weekend. A large northwest swell may arrive Tuesday night. Choppy surf will remain along east facing shores due to the breezy trade winds. Surf should gradually lower Thursday as the trades weaken. Minimal surf is expected along south facing shores.

World-wide Tropical Cyclone Activity

Here’s the latest Pacific Disaster Center (PDC) Weather Wall Presentation covering the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico…and the Caribbean Sea

Here’s the latest Pacific Disaster Center (PDC) Weather Wall Presentation covering the Pacific and Indian Oceans, including a tropical disturbance being referred to as Invest 93W…which has a low chance of developing.

>>> Atlantic Ocean: No active tropical cyclones

Here’s a satellite image of the Atlantic

>>> Gulf of Mexico: No active tropical cyclones

>>> Caribbean Sea: No active tropical cyclones

Here’s a satellite image of the Caribbean Sea…and the Gulf of Mexico

>>> Eastern Pacific: No active tropical cyclones

1.) Disorganized showers and thunderstorms continue in association with a well-defined low pressure system centered a little more than 100 miles southwest of Zihuatanejo, Mexico. Although tropical cyclone formation is not expected due to strong upper-level winds, the associated shower activity will continue to spread onshore and well inland over southwestern Mexico into this afternoon. Locally heavy rainfall and gusty winds will occur over portions of the Mexican states of Guerrero, Michoacan, Colima and Jalisco, and these rains could result in life-threatening flash floods and mudslides.

* Formation chance through 48 hours…low…near 0 percent

* Formation chance through 5 days…low…near 0 percent

Here’s the link to the National Hurricane Center (NHC)

>>> Central Pacific: No active tropical cyclones

Here’s the link to the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC)

>>> Northwest Pacific Ocean: No active tropical cyclones

>>> South Pacific Ocean: No active tropical cyclones

>>> North and South Indian Oceans / Arabian Sea: No active tropical cyclones

Here’s a link to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC)

Interesting: Stanford study shows regions increasingly suffer hot, dry conditions at the same time – A new study from Stanford University suggests that the kind of hot, dry conditions that can shrink crop yields, destabilize food prices and lay the groundwork for devastating wildfires are increasingly striking multiple regions simultaneously as a result of a warming climate.

According to the researchers, climate change has doubled the odds that a region will suffer a year that is both warm and dry compared to the average for that place during the middle of the 20th century. It’s also becoming more likely that dry and severely warm conditions will hit key agricultural regions in the same year, potentially making it harder for surpluses in one location to make up for low yields in another.

“When we look in the historical data at the key crop and pasture regions, we find that before anthropogenic climate change, there were very low odds that any two regions would experience those really severe conditions simultaneously,” said climate scientist Noah Diffenbaugh, the Kara J. Foundation professor in Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth) and senior author of the study published Nov. 28 in Science Advances. The study is titled “Multi-dimensional risk in a non-stationary climate: joint probability of increasingly severe warm and dry conditions.”

“The global marketplace provides a hedge against localized extremes, but we’re already seeing an erosion of that climate buffer as extremes have increased in response to global warming,” said Diffenbaugh, who is also the Kimmelman Family senior fellow in the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

The new study points to a future in which multiple regions are at risk of experiencing low crop yields simultaneously. That’s because, while some crops can thrive in a warm growing season, others – particularly grains – grow and mature too quickly when temperatures rise, consecutive dry days pile up and warmth persists overnight. As a result, hot-dry conditions tend to produce smaller harvests of major commodities, including wheat, rice, corn and soybeans.

The implications extend beyond agriculture. Those same hot, dry conditions can also exacerbate fire risk, drying out vegetation in the summer and autumn and fueling intense, fast-spreading wildfires like those that burned through more than 240,000 acres in California in November 2018.

Moving targets

The basic trend of global warming – 1 degree Celsius or 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit since the late 19th century – lends an intuitive logic to the study’s core findings. “If it’s getting warmer everywhere, then it’s more likely to be hot in two places at once,” Diffenbaugh explained, “and it’s probably also more likely to be hot when it’s also dry in two places at once.”

Yet despite that simple intuition, accounting for ongoing, interdependent changes in both precipitation and temperature in different locations through time presents a statistical challenge. As a result, many past analyses have looked at warm and dry events as independent phenomena, or at different regions as independent from one another.

That approach may underestimate the added risk due to human-caused global warming, as well as the social, ecological and economic benefits of curbing emissions. “When these extremes occur simultaneously, it exacerbates the adverse impacts beyond what any of them would have caused separately,” said Ali Sarhadi, the study’s lead author and a postdoctoral scholar in Diffenbaugh’s Climate and Earth System Dynamics Group at Stanford Earth.

Extremes becoming normal

The new study used historical data from the past century to quantify the odds that different regions experience hot and dry conditions in the same year. The analysis shows that before 1980, there was less than a 5 percent chance that two region pairs would experience extreme temperatures in a year that was also dry in both regions. However, in the past two decades, the odds have increased to as much as 20 percent for some region pairs.

For example, the odds that China and India – two of the world’s largest agricultural producers and the two most populous nations – both experience low precipitation and extremely warm temperatures in the same year have gone from less than 5 percent before 1980 to more than 15 percent today, Diffenbaugh said. “So, what used to be a rare occurrence can now be expected to occur with some regularity, and we have very strong evidence that global warming is the cause.”

In addition to their analyses of historical data, the authors also analyzed climate model projections of possible future global warming scenarios. They found that within a few decades, if the world continues on its current emissions trajectory, the odds that average temperatures will rise well beyond the range normally experienced in the middle of the 20th century could climb upward of 75 percent in many regions.

But achieving the goals outlined in the United Nations’ Paris climate agreement is likely to substantially reduce those risks, Sarhadi said. While the White House has announced its intention to withdraw the United States from the agreement, the study shows that achieving the emissions reduction targets in the 200-nation pact would allow the world to dramatically reduce the likelihood of compounding hot, dry conditions hitting multiple croplands across the world. “There are still options for mitigating these changes,” he said.

Planning for real risks

The framework built for this study represents a vital step in pinning down the risk associated with multiple climate extremes coming together in one region, where they can often compound one another. What were the chances, for example, that high temperatures, high winds and low humidity combined to create mega fire conditions in the past, and how have those odds changed as a result of global warming? That’s the sort of question the team’s framework will be able to answer. It’s a gravely urgent one for officials now reckoning with fires of historic scale and intensity in California.

“A lot of the events that stress infrastructure, and our disaster prevention and response systems, occur when multiple ingredients come together in the same place at the same time,” Diffenbaugh said. High storm surges and wind speeds with heavy rain can make the difference between a passing storm and a calamitous tropical cyclone; wind patterns and moisture levels in different parts of the atmosphere influence the severity of a rainstorm and associated flood risk.

A key challenge for decision-makers is understanding what to expect in a changing climate. That means honing in on joint probabilities, which are at the core of calculations that engineers, policy-makers, humanitarian aid providers and insurers use to allocate resources, set building codes and design evacuation plans and other disaster responses.

“People are making practical decisions based on the probabilities of different combinations of conditions,” Diffenbaugh said. “The default is to use the historical probabilities, but our research shows that assuming that those historical probabilities will continue into the future doesn’t accurately reflect the current or future risk.”

Email Glenn James:

Email Glenn James:

Diane Says:

Dear Glenn,

Nice coverage of the Mars InSight Landing in your “Interesting” section of Your website.

This will be a re-read for me at least 3 times!!!

Mahalo for teaching me just what I want to know…..and more🙏

Healthy Holidays,

Diane

Northern CA

~~~ Hi Diane, good to hear from you again, indeed, I found this Mars landing interesting as well, and will be curious to find out how it goes…as more information comes forward.

I’m happy to know that you are still a visitor to my site, I appreciate your letting me know.

Happy Holiday’s to you too!

Aloha, Glenn

Jay Says:

That was fascinating by Mars InSight…thanks. Good to see the ITCZ down where it belongs.

~~~ Hi Jay, yes, as I was mentioning to Diane above, this is fascinating stuff!

The ITCZ is well south now, down in the deeper tropics where it normally lives.

Happy Holiday’s!

Aloha, Glenn