Air Temperatures – The following maximum temperatures (F) were recorded across the state of Hawaii Thursday…along with the minimums Thursday:

77 – 69 Lihue, Kauai

82 – 70 Honolulu, Oahu

77 – 66 Molokai AP

81 – 68 Kahului AP, Maui

83 – 76 Kailua Kona

77 – 71 Hilo AP, Hawaii

Here are the latest 24-hour precipitation totals (inches) for each of the islands…as of Thursday:

1.40 Mount Waialeale, Kauai

2.38 Punaluu Stream, Oahu

1.92 Molokai

0.01 Lanai

0.00 Kahoolawe

3.67 West Wailuaiki, Maui

7.88 Kawainui Stream, Big Island

The following numbers represent the strongest wind gusts (mph)…as of Thursday:

31 Port Allen, Kauai

44 Oahu Forest NWR, Oahu

31 Molokai

39 Lanai

27 Kahoolawe

31 Kahului AP, Maui

35 Puu Mali, Big Island

Hawaii’s Mountains – Here’s a link to the live web cam on the summit of near 13,800 foot Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawaii. This web cam is available during the daylight hours here in the islands…and when there’s a big moon shining down during the night at times. Plus, during the nights you will be able to see stars, and the sunrise and sunset too…depending upon weather conditions.

Aloha Paragraphs

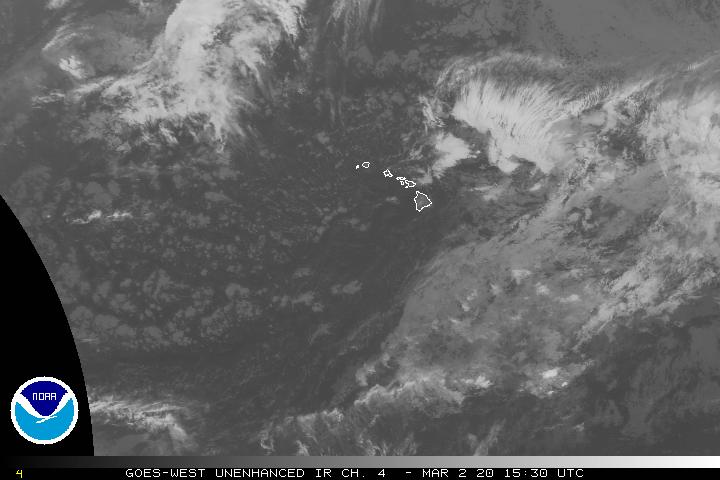

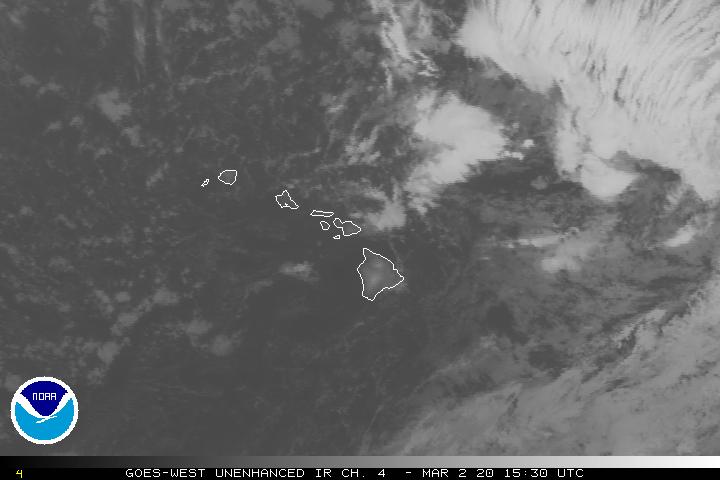

Low pressure system over the ocean far to the northeast…

with another low pressure cell far to the north

Weakening stationary cold front near the Big Island

Partly to mostly cloudy across the state

Showers falling locally, especially Oahu to the Big Island…

some are locally generous – looping radar image

Small Craft Advisory…channels from Oahu

down through the Big Island

~~~ Hawaii Weather Narrative ~~~

Locally strong and gusty trade winds…turning somewhat lighter Friday into the weekend. Here’s the latest weather map, showing the Hawaiian Islands, and the rest of the North Pacific Ocean. We find a high pressure system to the north of Hawaii…with associated ridge north of the islands. At the same time, we see low pressure systems north and northwest of the islands…along with the tail-end of a cold front over or near the Big Island. Strong and gusty trade winds are arriving in the wake of this front for the time being. This in turn will keep somewhat cooler than normal weather over the state. The trade winds will gradually ease up some Friday into the weekend….then pick up again early next week.

Here’s a wind profile…of the offshore waters around the islands – with a closer view

Here’s the Hawaiian Islands Sulfate Aerosol…animated graphic – showing vog forecast

Remnant showers from the recent cold front will keep conditions locally wet…especially windward and mountain slopes over the eastern islands and Oahu. The gusty winds following in the wake of the recent front will keep frequent windward showers in our weather picture, which will stretch over into the leeward sides…on the smaller islands at times locally. These winds, and their associated off and on showers will remain active into the weekend. The leeward sides will have clouds at times, and even a few showers, although less so than the windward sides. It looks like the trade winds will pick up a notch again early next week, with more passing windward showers arriving then.

Marine environment details: A small craft advisory, SCA, is up for all Hawaiian waters through this evening due to the locally strong trade winds. As the winds gradually weaken, the SCA is expected to be dropped for waters west of Oahu tonight.

Trade winds will produce rough surf along east facing shores…although the surf will subside as the trade winds weaken.

A new northwest swell arriving Saturday will produce surf near the advisory threshold by Sunday. Surf will remain small along the south shores.

Gradually lighter trade winds…small to medium surf

World-wide tropical cyclone activity:

>>> Atlantic Ocean: The last regularly scheduled Tropical Weather Outlook of the 2015 Atlantic hurricane season…has occurred. Routine issuance of the Tropical Weather Outlook will resume on June 1, 2016. During the off-season, Special Tropical Weather Outlooks will be issued if conditions warrant. Here’s the 2015 hurricane season summary

Here’s a satellite image of the Atlantic Ocean

>>> Caribbean Sea: The last regularly scheduled Tropical Weather Outlook of the 2015 Atlantic hurricane season…has occurred. Routine issuance of the Tropical Weather Outlook will resume on June 1, 2016. During the off-season, Special Tropical Weather Outlooks will be issued if conditions warrant.

>>> Gulf of Mexico: The last regularly scheduled Tropical Weather Outlook of the 2015 Atlantic hurricane season…has occurred. Routine issuance of the Tropical Weather Outlook will resume on June 1, 2016. During the off-season, Special Tropical Weather Outlooks will be issued if conditions warrant.

Here’s a satellite image of the Caribbean Sea…and the Gulf of Mexico

Here’s the link to the National Hurricane Center (NHC)

>>> Eastern Pacific: The last regularly scheduled Tropical Weather Outlook of the 2015 North Pacific hurricane season…has occurred. Routine issuance of the Tropical Weather Outlook will resume on May 15, 2016. During the off-season, Special Tropical Weather Outlooks will be issued if conditions warrant. Here’s the 2015 hurricane season summary

Here’s a wide satellite image that covers the entire area between Mexico, out through the central Pacific…to the International Dateline.

Here’s the link to the National Hurricane Center (NHC)

>>> Central Pacific: The central north Pacific hurricane season has officially ended. Routine issuance of the tropical weather outlook will resume on June 1, 2016. During the off-season, special tropical weather outlooks will be issued if conditions warrant. Here’s the 2015 hurricane season summary

Here’s a link to the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC)

>>> South Pacific Ocean: No active tropical cyclones

>>> North and South Indian Oceans / Arabian Sea: No active tropical cyclones

Here’s a link to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC)

Interesting: NASA examines El Nino’s impact on ocean’s food source – El Niño years can have a big impact on the littlest plants in the ocean, and NASA scientists are studying the relationship between the two.

In El Niño years, huge masses of warm water – equivalent to about half of the volume of the Mediterranean Sea – slosh east across the Pacific Ocean towards South America. While this warm water changes storm systems in the atmosphere, it also has an impact below the ocean’s surface. These impacts, which researchers can visualize with satellite data, can ripple up the food chain to fisheries and the livelihoods of fishermen.

El Niño’s mass of warm water puts a lid on the normal currents of cold, deep water that typically rise to the surface along the equator and off the coast of Chile and Peru, said Stephanie Uz, ocean scientist at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. In a process called upwelling, those cold waters normally bring up the nutrients that feed the tiny organisms, which form the base of the food chain.

“An El Niño basically stops the normal upwelling,” Uz said. “There’s a lot of starvation that happens to the marine food web.” These tiny plants, called phytoplankton, are fish food – without them, fish populations drop, and the fishing industries that many coastal regions depend on can collapse.

With NASA satellite data, and ocean color software called SeaDAS, developed at the Ocean Biology Processing Group at Goddard, Uz has been mapping where these important phytoplankton appear. Orbiting instruments like the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectrometer on the Aqua satellite, and the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite on the Suomi NPP satellite collect data on the color of the ocean. From shades of blue and green, scientists can calculate the amount of green chlorophyll – and therefore the amount of phytoplankton present.

The ocean color maps, based on a month’s worth of satellite data, can show that El Niño impact on phytoplankton. In December 2015, at the peak of the current El Niño event, there was more blue – and less green chlorophyll – in the Pacific Ocean off of Peru and Chile, compared to the previous year. Uz and her colleagues are also watching as the El Niño weakens this spring, to see when and where the phytoplankton reappear as the upwelling cold water brings nutrients back to the region.

“They can pop back up pretty quickly, once they have a source of nutrients,” Uz said.

Researchers can also examine the differences in ocean color between two different El Niño events. During the large 1997-1998 El Niño event, the green chlorophyll virtually disappeared from the coast of Chile. This year’s event, while it caused a drop in chlorophyll primarily along the equator, was much less severe for the coastal phytoplankton population. The reason – the warmer-than-normal waters associated with the two El Niño events were centered in different geographical locations. In 1997-1998, the biggest ocean temperature abnormalities were in the eastern Pacific Ocean; this year the focus was in the central ocean. This difference impacts where the phytoplankton can feed on nutrients, and where the fish can feed on phytoplankton.

“When you have an East Pacific El Niño, like 1997-1998, it has a much bigger impact on the fisheries off of South America,” Uz said. But Central Pacific El Niño events, like this year’s, still have an impact on ocean ecosystems, just with a shift in location. Researchers are noting reduced food available along the food chain around the Galapagos Islands, for example. And there has been a drop in phytoplankton off the coast of South America, just not as dramatically as before.

Scientists have more tools on hand to study this El Niño, and can study more elements of the event, Uz said. They’re putting these tools to use to ask questions not just about ocean ecology, but about the carbon cycle as well.

“We know how important phytoplankton are for the marine food web, and we’re trying to understand their role as a carbon pump,” Uz said. The carbon pump refers to one of the ways the Earth system removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. When phytoplankton die, their carbon-based bodies sink to the ocean floor, where they can remain for millions of years. El Niño is a naturally occurring disruption to the typical ocean currents, she said – so it’s important to understand the phenomenon to better attribute what occurs naturally, and what occurs due to human-caused disruptions to the system.

Other scientists at Goddard are investigating ways to forecast the ebbs and flows of nutrients using the center’s supercomputers, incorporating data like winds, sea surface temperatures, air pressures and more.

“It’s like weather forecasts, but for bionutrients and phytoplankton in the ocean,” said Cecile Rousseaux, an ocean modeler with Goddard’s Global Modeling and Assimilation Office. The forecasts could help fisheries managers estimate how good the catch could be in a particular year, she said, since fish populations depend on phytoplankton populations. The 1997-1998 El Niño led to a major collapse in the anchovy fishery off of Chile, which caused economic hardships for fishermen along the coast.

So far, Rousseaux said, the phytoplankton forecast models haven’t shown any collapses for the 2015-2016 El Niño, possibly because the warm water isn’t reaching as far east in the Pacific this time around. The forecast of phytoplankton populations effort is a relatively new effort, she said, so it’s too soon to make definite forecasts. But the data so far, from the modeling group and others, show conditions returning to a more normal state this spring.

The next step for the model, she said, is to try to determine which individual species of phytoplankton will bloom where, based on nutrient amounts, temperatures and other factors – using satellites and other tools to determine which kind of microscopic plant is where.

“We rely on satellite data, but this will go one step further and give us even more information,” Rousseaux said.

Email Glenn James:

Email Glenn James: