Air Temperatures – The following high temperatures (F) were recorded across the state of Hawaii Wednesday…along with the low temperatures Wednesday:

80 – 72 Lihue, Kauai

82 – 71 Honolulu, Oahu

82 – 70 Kahului AP, Maui

79 – 68 Kailua Kona AP

78 – 64 Hilo AP, Hawaii

Here are the latest 24-hour precipitation totals (in inches) for each of the islands as of Wednesday evening:

1.55 Kilohana, Kauai

0.79 Manoa Lyon Arboretum, Oahu

0.22 Molokai

0.04 Lanai

0.16 Kahoolawe

1.34 Puu Kukui, Maui

1.96 Saddle Quarry, Big Island

The following numbers represent the strongest wind gusts (mph) as of Wednesday evening:

29 Lihue, Kauai

35 Oahu Forest NWR, Oahu

27 Molokai

33 Lanai

27 Kahoolawe

30 Maalaea Bay, Maui

42 Kohala Ranch, Big Island

Here’s a wind profile of the Pacific Ocean – Closer view of the islands

Hawaii’s Mountains – Here’s a link to the live webcam on the summit of our tallest mountain Mauna Kea (nearly 13,800 feet high) on the Big Island of Hawaii. This webcam is available during the daylight hours here in the islands, and at night whenever there’s a big moon shining down. Also, at night you will be able to see the stars — and the sunrise and sunset too — depending upon weather conditions.

Aloha Paragraphs

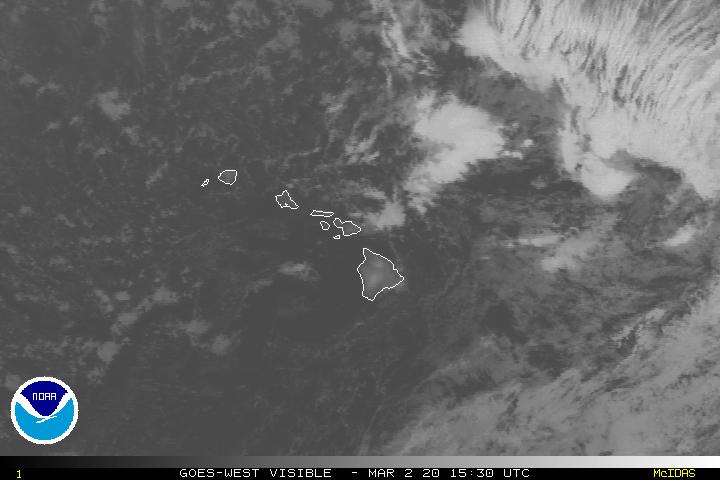

Winter’s active weather is staying away from Hawaii…although a weak cold front is approaching from the north

Thunderstorms far south and southwest…and west of Hawaii

Low clouds bringing showers to the islands locally…continuing tonight

Showers locally…mostly windward sections and offshore – Looping radar image

Small Craft Advisory…windiest coasts and channels around the state

Gale Warning…Northern offshore waters (40-240 nautical miles) tonight and Thursday

~~~ Hawaii Weather Narrative ~~~

Trade winds prevail…although will weaken some during the weekend. Here’s the latest weather map, showing a moderately strong high pressure system northeast of Hawaii, with a second much stronger high pressure cell to the north-northwest. At the same time we see a low pressure center far to the northeast, with a trailing cold front. As a result, the trade winds will continue to be our primary weather influence, which are expected to remain a bit gusty through Friday. This windy episode will finally give way to lighter breezes during the holiday weekend into early next year.

An early winter trade wind weather pattern is holding firm…with off and on increases in windward showers. This prolonged trade wind weather pattern will last through the end of the year, with a weak frontal cloud band or two, or at least their tail ends arriving along the way. Showers will most effectively focus their efforts along our windward coasts and slopes…none of which is expected to be heavy. The first of these fronts will bring showers our way early Friday, first on Kauai. In sum, generally peaceful weather conditions will stick around through the rest of this year, with off and on showers extending into the first few days of 2017.

Marine environment details: Fresh to locally strong trade winds will hold on, as a very strong, 1044 mb high located north-northwest of the islands, is taking the place of a weakening high pressure cell to the northeast of the state. Numerical models suggest little change in the winds into Thursday as a front approaches from the north.

The front will reach Kauai late Thursday night then slowly advance to Maui County Friday. Expect strong and gusty northeast trade winds and large, rough seas along and behind the front…as strong high pressure settles north of the state. A marked decrease in trade winds and seas will occur during the weekend and early next week…with the SCA likely coming down.

Moderate trade wind swell will hold Thursday, with a large and rough north-northeast swell building late Thursday afternoon or evening. A High Surf Advisory (HSA) will likely be needed on Thursday night and Friday for exposed east facing shores from Kauai to Maui, but with the bulk of this swell affecting the western end of the state, the eastern shores of the Big Island may not experience advisory level surf. These large and rough seas will coincide with the strongest winds, contributing to the need for an SCA. Additional pulses of north-northeast swell are expected into early next week, possibly leading to advisory level surf along some east facing shores and possible harbor surge on Sunday night or Monday.

Locally gusty trade winds continuing

World-wide tropical cyclone activity…with storms showing up when active

![]()

>>> Atlantic Ocean: The 2016 hurricane season has ended

Here’s a satellite image of the Atlantic Ocean

>>> Caribbean: The 2016 hurricane season has ended

>>> Gulf of Mexico: The 2016 hurricane season has ended

Here’s a satellite image of the Caribbean Sea…and the Gulf of Mexico

Here’s the link to the National Hurricane Center (NHC)

>>> Eastern Pacific: The 2016 hurricane season has ended

Here’s a wide satellite image that covers the entire area between Mexico, out through the central Pacific…to the International Dateline.

Here’s the link to the National Hurricane Center (NHC)

>>> Central Pacific: The 2016 hurricane season has ended

Here’s the NOAA 2016 Hurricane Season Summary for the Central Pacific Basin

Here’s a link to the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC)

>>> South Pacific Ocean: No active tropical cyclones

>>> North and South Indian Oceans / Arabian Sea: No active tropical cyclones

Here’s a link to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC)

Interesting What Satellites Can Tell Us About How Animals Will Fare in a Changing Climate – From the Arctic to the Mojave Desert, terrestrial and marine habitats are rapidly changing. These changes impact animals that are adapted to specific ecological niches, sometimes displacing them or reducing their numbers. From their privileged vantage point, satellites are particularly well-suited to observe habitat transformation and help scientists forecast impacts on the distribution, abundance and migration of animals.

In a press conference Monday at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco, three researchers discussed how detailed satellite observations have facilitated ecological studies of change over time. The presenters discussed how changes in Arctic sea ice cover have helped scientists predict a 30 percent drop in the global population of polar bears over the next 35 years. They also talked about how satellite imagery of dwindling plant productivity due to droughts in North America gives hints of how both migratory herbivores and their predators will fare. Finally, they also discussed how satellite data on plant growth indicate that the concentration of wild reindeer herds in the far north of Russia has not led to overgrazing of their environment, as previously thought.

Long-term polar bear declines

Polar bears depend on sea ice for nearly all aspects of their life, including hunting, traveling and breeding. Satellites from NASA and other agencies have been tracking sea ice changes since 1979, and the data show that Arctic sea ice has been shrinking at an average rate of about 20,500 square miles (53,100 square kilometers) per year over the 1979-2015 period. Currently, the status of polar bear subpopulations is variable; in some areas of the Arctic, polar bear numbers are likely declining, but in others, they appear to be stable or possibly growing.

“When we look forward several decades, climate models predict such profound loss of Arctic sea ice that there’s little doubt this will negatively affect polar bears throughout much of their range, because of their critical dependence on sea ice,” said Kristin Laidre, a researcher at the University of Washington’s Polar Science Center in Seattle and co-author of a study on projections of the global polar bear population. Eric Regehr of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Anchorage, Alaska, led the study, which was published on December 7 in the journal Biology Letters.

“On short time scales, we can have variable responses to the loss of sea ice among subpopulations of polar bears,” Laidre said. “For example, in some parts of the Arctic, such as the Chukchi Sea, polar bears appear healthy, fat and reproducing well — this may be because this area is very ecologically productive, so you can lose some ice before seeing negative effects on bears. In other parts of the Arctic, like western Hudson Bay, studies have shown that survival and reproduction have declined as the availability of sea ice declines.”

Regehr, Laidre and their colleagues’ results are the product of the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List assessment for polar bears. To determine the level of threat to a species, IUCN requests scientists to project what the species population numbers will be after three generations. Using data collected from adult females in 11 subpopulations of polar bears across the Arctic, Regehr and Laidre’s team calculated the generation length for polar bears—the average age of reproducing adult females—to be 11.5 years. They then used the satellite record of Arctic sea ice extent to calculate the rates of sea ice loss and then projected those rates into the future, to estimate how much more the sea ice cover may shrink in approximately three polar bear generations, or 35 years.

Lastly, the scientists evaluated different scenarios for the relationships between polar bear abundance and sea ice. In one of them, the bear numbers declined directly proportionally with sea ice. In the other scenarios, the researchers used the existing, albeit scarce, data on how polar bear abundance has changed with respect to sea ice loss, using all available data from polar bear subpopulations in the four existing polar bear eco-regions, and projected forward these observed trends. They concluded that, based on a median value across all scenarios, there’s a high probability of a 30 percent decline in the global population of polar bears over the next three to four decades, which supports listing the species as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List.

“It is difficult to predict what population numbers will be in the future, especially for animals that live in vast and remote regions,” Regehr said. “But at the end of the day, polar bears need sea ice to be polar bears. This study adds to a growing body of evidence that the species will likely face large declines as loss of their habitat continues.”

Drought and mountain lions

The southwestern United States is expected to become more prone to droughts with climate change. The resulting loss of vegetation will not only impact herbivores like mule deer; their main predator, mountain lions, might take an even larger hit.

To estimate the numbers and distribution of mule deer and mountain lions in Utah, Nevada and Arizona, David Stoner, a wildlife ecologist at Utah State University in Logan, Utah, used imagery of plant productivity from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, flown on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites, plus radio-telemetry measurements of animal density and movements. He found that there is a very strong relationship between plant productivity and deer and mountain lion density.

“Measuring abundance of mule deer in the western United States is logistically difficult, hazardous and very expensive. For mountain lions, it’s even worse,” Stoner said. “But measuring changes in vegetation is relatively easy and more affordable. With this research, we’ve provided a model that wildlife managers can use to estimate the density of deer and mountain lions, two big game species of great economic importance.”

Using maps of vegetation productivity during a severe drought that occurred in the southwestern United States in 2002, Stoner modeled what would be the deer and mountain lion distribution and abundance, should extreme drought become the norm.

“During 2002, there was a 30 percent decrease from the historical record mean in precipitation,” Stoner said. “Using measurements of vegetation stressed by drought, our model predicted a 22 percent decrease in deer density. For mountain lions, the decline was 43 percent. Mountain lions occur at far lower densities than deer, and so any loss of their prey can have disporportionate impacts on their reproductive rates and overall abundance.”

Mule deer are popular game animals, bringing in hundreds of millions of dollars to rural areas through recreational hunting and tourism. But deer can also have adverse economic impacts; they cause vehicle collisions, devour crops and damage gardens.

“Droughts will make human landscapes more attractive to deer, because farms and suburban areas are irrigated and would remain fairly green,” Stoner said. “And mountain lions will go wherever the deer are. We’re going to lose some of the economic benefits of having those animals, because they’ll be fewer of them, but the costs are going to increase because the remaining animals will be attracted to cities and farms.”

Longer journeys for wild reindeer

The Taimyr reindeer herd in the northernmost region of Russia is the largest wild reindeer herd in the world and a key of source of food for the indigenous population of the Taimyr Peninsula.

“Reindeer populations are declining all over the world, in some places catastrophically; in Taimyr, there has been an about 40 percent drop since 2000 and the herd is now at 600,000 animals,” said Andrey Petrov, an associate professor at the University of Northern Iowa, in Cedar Falls.

Petrov examined historical data going back to 1969 and determined that there are ongoing changes in the distribution and migration patterns of the wild reindeer due to climate change and human pressure. The reindeer have moved east, away from human activity. At the same time, the herd is now traveling farther north and higher in elevation during the summer, possibly to avoid increasing temperatures and more abundant mosquitoes.

“Taimyr reindeer now have to travel longer distances between their winter and summer grounds, and this is causing a higher calf mortality,” Petrov said. “Other factors contributing to the higher mortality are the increased mosquito harassment and the fact that rivers are opening earlier than before and the animals have to cross them during their migration.”

Petrov also used imagery from the NASA/United States Geological Survey Landsat satellite program to determine how the presence of reindeer in their summer grounds impacts vegetation. He found that, as expected, plant biomass decreased while the reindeer were grazing, but it bounced back a few weeks after the animals left the area. This finding argues against overgrazing as a possible factor for the Taimyr reindeer population decline that occurred after 2000.

Email Glenn James:

Email Glenn James:

woody adamz Says:

Nice sunset pic Glen and, I’ve seen pictures of Polar Bears so skinny that they could barely move AND, stuck on small sea ice with no recourse. It brought tears for the ignorance that allows “Profit before LIFE” .Not a smart modus long term….Hope, Pray and Do what we can…..A Happy Hoppy New Years to ALL……!!!!

~~~ Hi Woody, good to hear from you again. Thanks for your well wishes to all of us for the New Year, coming up soon! Here’s sending positive thoughts back in your direction as well.

Aloha, Glenn