Air Temperatures – The following maximum temperatures (F) were recorded across the state of Hawaii Thursday…along with the low temperatures Thursday:

88 – 77 Lihue, Kauai

88 – 75 Honolulu, Oahu

85 – 75 Molokai AP

89 – 73 Kahului AP, Maui

87 – 76 Kona AP

84 – 69 Hilo AP, Hawaii

Here are the latest 24-hour precipitation totals (inches) for each of the islands…Thursday evening:

0.61 Mount Waialeale, Kauai

0.76 Moanalua RG 1, Oahu

0.15 Molokai

0.00 Lanai

0.00 Kahoolawe

0.11 West Wailuaiki, Maui

0.09 Kealakekua, Big Island

The following numbers represent the strongest wind gusts (mph)…Thursday evening:

29 Port Allen, Kauai

35 Oahu Forest NWR, Oahu

25 Molokai

27 Lanai

31 Kahoolawe

36 Maalaea Bay, Maui

29 Kealakomo, Big Island

Hawaii’s Mountains – Here’s a link to the live web cam on the summit of near 13,800 foot Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawaii. This web cam is available during the daylight hours here in the islands…and when there’s a big moon shining down during the night at times. Plus, during the nights you will be able to see stars, and the sunrise and sunset too…depending upon weather conditions.

Aloha Paragraphs

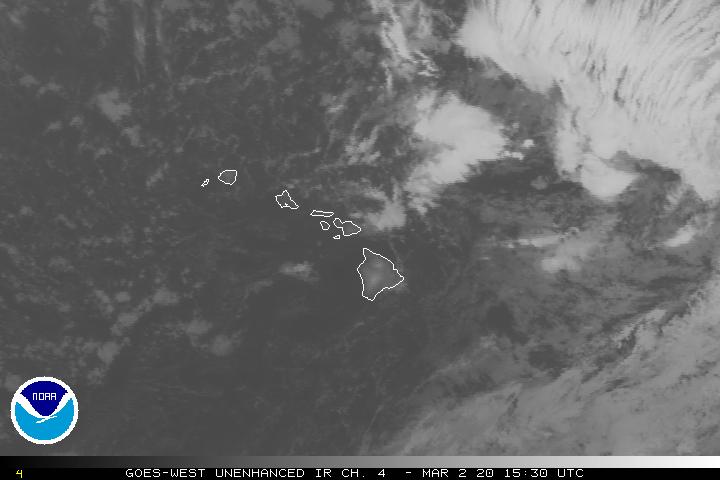

A tropical disturbance is located well southeast of the islands

Thunderstorms south…and that disturbance southeast of the state

Scattered low clouds…with Cirrus clouds over parts of the southern islands

Showers mostly windward and mountains…some will be rather generous – Looping radar image

Small Craft Advisory…Maalaea Bay, Pailolo and Alenuihaha Channels

~~~ Hawaii Weather Narrative ~~~

Moderately strong trade winds into next week. Here’s the latest weather map, showing a rather strong, near 1034 millibar high pressure system far to our northeast, the source of our local trades. There will be minor day-to-day variations in speed and direction of these trade winds…although no major deviations one way or the other for the time being.

A trade wind weather pattern prevails over the Hawaiian Islands. A weak upper level low pressure system is forecast to move near the islands soon. This will result in the atmosphere becoming less stable, which would prompt showers to become a bit more active. Meanwhile, the models are showing an area of moisture coming up from the deeper tropics, towards the islands right after the weekend. This area would then pass by just south of the state, or even shift over parts of the island chain. If this outlook comes to pass, we could see an additional increase in showers. As always, these longer range outlooks can and often do require adjustments and changes, stay tuned.

Here’s a wind profile…of the offshore waters around the islands – with a closer view

Here’s the Hawaiian Islands Sulfate Aerosol animated graphic – showing vog forecast

Marine environment details: A Small Craft Advisory remains posted for the typical windy waters around Maui County and the Big Island. This may be lowered as the trade winds drop off a bit Friday.

There will be a series of small to medium size south swells through the remainder of this week, and on into the middle of next week. Easterly trade winds will continue to produce choppy surf along east facing shores throughout the forecast period. An early season northwest swell is forecast to gradually fill in Monday, peak on Tuesday…then lower gradually Wednesday.

Pleasant weather…with refreshing trade winds

World-wide tropical cyclone activity..

![]()

>>> Atlantic Ocean: No active tropical cyclones

1.) A large area of disturbed weather associated with a westward-moving tropical wave is located about 1200 miles east of the Lesser Antilles. This system is gradually becoming better organized, and conditions are forecast to be favorable for a tropical depression to form this weekend or early next week. This disturbance is expected to move toward the west-northwest and then northwest over the central Atlantic during the next several days.

This disturbance is being called Invest 94L, here’s a satellite image and what the computer models are showing

* Formation chance through 48 hours…low…30 percent

* Formation chance through 5 days…high…70 percent

Here’s a satellite image of the Atlantic Ocean

>>> Caribbean: No active tropical cyclones

1.) Cloudiness and showers located just north of the northern Leeward Islands are spreading west-northwestward with no signs of organization. Environmental conditions are not expected to be conducive for significant development.

* Formation chance through 48 hours…low…10 percent

* Formation chance through 5 days…low…10 percent

2.) A small area of disturbed weather associated with a weak low has formed between Cuba and the western Bahamas. This activity is expected to spread westward across southern Florida and the Florida Keys later today and Saturday. Upper-level winds are not favorable for additional development.

* Formation chance through 48 hours…low…10 percent

* Formation chance through 5 days…low…10 percent

>>> Gulf of Mexico: No active tropical cyclones

Here’s a satellite image of the Caribbean Sea…and the Gulf of Mexico

Here’s the link to the National Hurricane Center (NHC)

>>> Eastern Pacific: No active tropical cyclones

1.) A broad area of low pressure is centered about 850 miles south of the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula. Although the associated shower and thunderstorm activity is still disorganized, environmental conditions are conducive for gradual development, and a tropical depression is likely to form late this weekend or early next week while the low moves west-northwestward at 10 to 15 mph.

Here’s a satellite image of what is being referred to as Invest 92E…and what the computer models are showing

* Formation chance through 48 hours…medium…50 percent

* Formation chance through 5 days…high…80 percent

Here’s a wide satellite image that covers the entire area between Mexico, out through the central Pacific…to the International Dateline.

Here’s the link to the National Hurricane Center (NHC)

>>> Central Pacific: No active tropical cyclones

1.) Disorganized showers and thunderstorms continue to develop around a weak surface low located about 700 miles southeast of Hilo, Hawaii. Environmental conditions may support some slow development of this system during the next couple of days as it moves slowly to the northwest.

* Formation chance through 48 hours…low…near 10 percent

Here’s a link to the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC)

Tropical Depression 16W remains active, located approximately 175 NM west-southwest of Andersen AFB, Guam. Here’s the JTWC graphical track map, a satellite image…and what the computer models are showing

>>> South Pacific Ocean: No active tropical cyclones

>>> North and South Indian Oceans / Arabian Sea: No active tropical cyclones

Here’s a link to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC)

Interesting: ‘Little Doubt’ Typhoons Have Become More Intense, Study Finds – In the Northwest Pacific, already a hotspot for tropical cyclones, the storms that strike East and Southeast Asia have been intensifying more than those that stay out at sea over the last four decades, a new study finds.

The proportion of land falling storms that reach Category 4 or 5 strength — the storms that wreak the most damage, as recent examples like 2013’s devastating Super Typhoon Haiyan show — has doubled and even tripled in some areas of the basin, researchers found. The increases seem to be the result of faster intensification linked to warmer ocean waters in coastal areas.

The findings, detailed in the journal Nature Geoscience, are in line with the broader increase in the most intense tropical cyclones expected with rising global temperatures, though these trends have not yet specifically been linked to human-caused climate change.

The Northwest Pacific normally sees the most tropical cyclone activity of any ocean basin because of the deep well of ocean heat available to fuel typhoons, as such storms are called there.

The new work is an outgrowth of a previous study by the same researchers that found that typhoon intensity had increased basin-wide since the late 1970s and suggested that another 14 percent increase in intensity could be expected by the end of the century, as the ocean takes up most of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases.

Wei Mei, a tropical cyclone and climate researcher at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said that he and his colleagues were curious if typhoons in some parts of the basin were intensifying more than others. To investigate this, they grouped the typhoons into clusters based on where they formed and the paths they followed.

They found that the clusters that had the most land falling hurricanes showed much clearer increases in intensity than those where most storms stayed out at sea. The cluster with the biggest trend had a 15 percent increase in intensity and, as part of that trend, saw the number of Category 4 and 5 storms increase from about one per year in the late 1970s to more than four per year recently.

The researchers wanted to figure out whether the higher intensities were due to the typhoons intensifying over a longer period of time or because they were doing so faster. They found that for the clusters with the biggest increases, typhoons were intensifying more than 60 percent faster since the late 1970s, but saw no major change in the rate for the others.

“The results leave little doubt that there are more high intensity events affecting Southeast Asia and China, and these are also intensifying more rapidly,” MIT’s Kerry Emanuel, who has been studying the links between hurricanes and climate change for more than a decade, said in an email. Emanuel provided some material to the researchers, but was not otherwise involved with the study.

Digging further into the possible causes for the trends they saw, the researchers linked the faster intensification rates of landfalling typhoons to higher ocean temperatures in coastal areas. Those warmer waters were ratcheting up the potential intensity of storms, or the theoretical maximum intensity they could achieve given the particular ocean temperatures and atmospheric environment. (Other factors, such as dry air or wind shear, often keep storms from reaching that potential maximum.)

Effectively, the higher potential intensity allowed for deeper convection — the engine at the heart of tropical systems — and therefore more rapid intensification. (The results also jibe with other work that has shown a poleward shift in where potential intensities reach their peak, effectively suggesting that the tropics are becoming less favorable to such storms and higher latitudes more favorable.)

Climate Change Link Uncertain

But what is causing the warmer oceans along the coast is not yet clear. The higher water temperatures could be due to climate patterns that vary naturally, climate change-driven warming, or some combination of the two.

“With such a short record it is impossible to distinguish between natural decadal variability and [any] anthropogenic signal,” Suzana Camargo, a hurricane-climate researcher at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said in an email. “It will be important to do more studies to try to sort out this issue.”

Mei said that he and his colleagues hope to do an attribution study using climate models to see if they can pinpoint any role of warming in the trends they have observed.

Climate models do suggest, however, that warming will continue in these ocean regions, the study researchers note, which would suggest that even more land falling typhoons would fall into the highest categories and would undergo more rapid intensification. This is of great concern because of the enormous damage these storms can do, as well as the difficulties forecasters still have in predicting when storms will quickly intensify.

“Even with perfect forecasts, intense storms tend to have the biggest impacts,” Camargo said. “If you compound [that] with forecast problems, then it’s even a bigger issue.”

Email Glenn James:

Email Glenn James: